I moved to New York in 1987 and immediately noticed how everyone talked about leaving.

You’d walk up to people chatting at a party and hear someone going on about how the art scene in Cleveland was so much more happening. Or how much space you can get for your rent in Baltimore.

Almost everyone I got to know was toying with the opportunity to make life better or easier by just getting out — an MFA program, a job at a think tank, blah, blah, blah.

Most often the conversation would circle back to all the stuff you couldn’t leave. Buying hot bagels after a night of drinking. Walking into some hole in the wall to find John Lurie sitting in on sax. Dropping by MOMA to look at a few Picassos whenever. Buying Haagen Dazs at 3am. Eating at your favorite dim sum place in Chinatown.

The Haagen Dazs thing is funny. For me, it was still “fancy” ice cream. Back in Mississippi, you couldn’t get it just anywhere. So to be able to run downstairs and buy it at the corner at 3am was the height of decadence.

So you’d recite your list of stuff then sigh and say, “I’m just a slave of New York.”

But more deeply, for most of us, it was that feeling of being inside our favorite New York movie. I moved to New York a year after Hannah and Her Sisters came out, and that’s exactly how the city felt to me. If you had to do something that took you to Times Square, you felt like you were in Taxi Driver or Midnight Cowboy. Every time you crossed a busy street, you wanted to shout, “I’m walking here!”

In the back of your mind, every conversation made you feel like you were in a New Yorker cartoon.

This gave you a great feeling of being in an upside down world where all the pretensions and fantasies you hid back in Missouri or Nebraska were normal, which, for you, meant that New York was the right-side up world.

And all of us, in our hearts, as the taxi bumped us home in the wee hours, even if we were alone and blue, we gazed out at gated stores and open bars and whispered “I’m a slave of New York.”

“Of” not “to,” by the way.

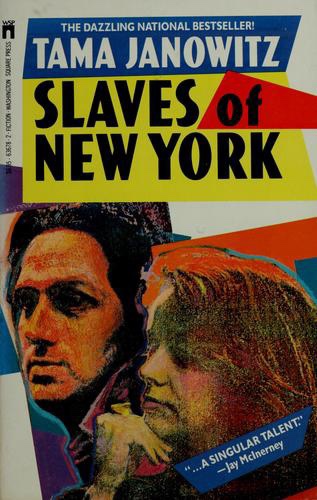

The phrase we used came from a story called “Slaves of New York” that had been a big hit a year or so earlier. I think the original meaning was a little different. You were a slave residing in New York. You were being a slave in the city of New York.

Yes, being in New York was itself a big part of why you were a slave, but you were a slave “to” something more specific. A landlord. A job. A lover.

But the people I met had re-purposed the phrase to express how you become a slave “to” New York itself, to the surprises, the adrenaline rushes, the drama and, mostly, the stuff.

What I didn’t anticipate was how you can become a slave of New York at the core of your psyche. How you can wake up one day and feel that you couldn’t live anywhere else. Literally. That you’d be dysfunctional in St. Louis, Charlotte or Kalamazoo.

I made this discovery after an experience on the crosstown shuttle.

We are in the Times Square station. Late 1980s.

The doors are about to close when this odd little man gets on. Well, he’s short but not little. He has a huge belly in a yellow Crazy Eddie t-shirt.

In case you don’t know, Crazy Eddie was an electronics chain. TVs. Stereos. Microwaves. And the prices were so low it was “crazy.” The logo was this cartoon guy who looked like a Robert Crumb drawing, cross-eyed with a polka dot bow tie.

And this guy on the shuttle is kind of like an older, obese version of the Crazy Eddie logo guy. He’s what the Crazy Eddie logo guy turned into at 50. Wild Einstein hair. Lunatic smile that expresses only confusion. He has thick glasses in heavy frames. He breathes through his mouth. His arms hang down slack around his enormous belly.

Right as he shuffles onto the car, he shouts … and I mean at the top of his lungs … all nasal whine with a faint lisp … he shouts: “DOES ANYONE KNOW HOW TO GET TO 23 PARK AVENUE?!?”

Okay, so if you know the subway system, you’re picturing what he has to do. We’re at Times Square. And we’re already on the shuttle. This guy wants to go to Park Avenue. He’s exactly where he needs to be.

This is 1987. Nobody has Google Maps on a Star Trek device in his pocket. So we don’t known the exact cross street for 23 Park Avenue. He probably needs to transfer to the 6 and go one stop down to 33rd.

But he 100% needs to be on the crosstown shuttle. He needs to go to Grand Central.

We all know what he needs to do.

He needs to go to Grand Central.

But this guy is clearly a kook. I don’t know if he escaped from Bellevue, but he’s obviously nutty and who wants to deal with a kook?

So nobody wants to engage. If he were a tourist with a map and a Midwestern smile, you could talk to him. But only grief will come from dealing with a kook.

And the doors are closing … bing bong. The train has now inexorably moved away from any other option. The shuttle has one destination: Grand Central.

Keep this in mind. We are on a train that only goes to Grand Central.

So the closest person to Crazy Eddie sort of mumbles, “You’re good.”

“WHY AM I GOOD?” he screams back.

“This is the right train.”

“DOES THIS TRAIN GO TO 23 PARK AVENUE?!?”

“Well, it goes to Grand Central, but then you …”

“I DON’T NEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEED GRAND CENTRAL!!!!!!!”

He screams this with his whole body, the way a dog barks. Rising up on his toes. Waving his hands at the end of his floppy dangling arms.

Then he shouts again: “DOES ANYONE KNOW HOW TO GET TO 23 PARK AVENUE?!?”

Okay. Now everybody knows that we’re stuck with this for the whole ride.

We’re on a train that only goes to Grand Central, and he doesn’t neeeeeed Grand Central.

Another person says, “You have to transfer to the Downtown 6.

“I transfer?”

“Yeah.”

“Okay.”

Hm. Great. Maybe we’re in the clear. That’s all it was. He didn’t realize that Grand Central is just a connection point. Not a final destination. He just didn’t get that.

“But where does THIS train go?” Crazy Eddie asks.

“Grand Cen –“

“I DON’T NEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEED GRAND CENTRAL!!!!!! DOES ANYONE KNOW HOW TO GET TO 23 PARK AVENUE?”

Now here’s the thing. My whole life had just fallen apart. I was having a nervous breakdown.

I was watching this scene already on the verge of hysterical tears. Nerves shattered.

Earlier that morning, I emerged from the subway onto 116th Street at the gates of Columbia University. My job was four blocks north on 120th.

I stood paralyzed for a long minute then started walking south. With that first step in the wrong direction I knew that I had quit my job. It never entered my mind to just call in sick. I was quitting. It was a shitty job, but in truth I was quitting everything. I was QUITTING. And I was quitting because I was broken.

To offer no explanation about this breakdown would be a little lame, but this poses a dilemma. On one hand, my troubles had pushed me to this point where I snapped. On the other hand, those troubles weren’t particularly dramatic for an outside observer. No one died. There was no dire medical diagnosis.

To understand how this subway instance made me realize that I was a slave of New York, I need you to have a sense of how shattered I was, but I don’t want to bore you talking about a girlfriend I had 30 years ago or my disappointed dreams of being a rock star.

It would be cool if I could offer a link where you could download directly into your brain the experience of reading a brilliant novel about my coming of age. Some great piece of writing that made my relatively average experience as a young man iconic and mythical and universal. Catcher in the Rye.

Picture a cover with a photo of the Brooklyn Bridge from the street below. Thick fog. A Polaroid found in the bottom of an old drawer.

In a flash, it would be as though you followed me from my first time plucking a guitar string as a child to recording my first big record in a professional studio. You’d be there with me in the gravel parking lot in Starkville, Mississippi, waiting for the bus to Memphis where I was going to board a plane to New York.

Via a tour de force of spare, crystalline prose, you’d emerge from the trees to enter the loop above the Lincoln Tunnel and see the Manhattan skyscrapers gleaming in the sun across the river.

You’d see my future girlfriend’s eyes glancing coyly back as she goes through the turnstile ahead of me. You’d see us running around Central Park with our guitars. And you’d hear in our first meaningful chat, on a bench in the twilight, breathing the urine aroma from the horses at the Plaza, the misery to come. You’d fly with us to make a record in Brussels and down to Georgia to meet her Atticus Finch-like father. And you’d see long before the protagonist (me) how this relationship was throwing him back into the same psychological gulag he’d fought so hard to escape.

You’d read in despair as the episodes of dysfunctionality cut deeper and deeper. You’d see his psyche coming apart at the seams. When he tells the girl about a tip he got about a “steady” and “solid” job at Columbia University, you are literally shouting “NOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!” at the book. Noooooooooo!!! Don’t take a shitty job to save this doomed relationship!!!

And you’re right there with him, stunned and demoralized by this soul-sucking job, when the girl confesses that she’s been in an secret abusive relationship with a mutual friend he deeply admired.

Coming into the day in question on the crosstown shuttle, you’d trudge with our hero, the morning after his girlfriend’s terrible confession, from his cold loft in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge, up Henry Street to the subway in the Saint George Hotel. You’d clack along on the train uptown, sensing as a reader that the story is finally coming to a head and wondering “Will he actually keep going like this?”

He emerges onto the busy Broadway sidewalk at Columbia in the brisk morning. But he stands frozen as people flow around him. If he can take one step north toward 120th Street, toward his office, then his powers of denial are still hanging on. But he turns and heads south on Broadway. Our protagonist has stepped over the edge. He’s stepped into the chaos that in truth always surrounds us, waiting to swallow us, waiting to demolish sanity, to demolish meaning, to demolish reality, to demolish God.

I walked in a panic for many blocks before going down into the subway.

And what you have to remember is how insane, brutal, noisy and dirty New York can feel when you’ve moved here from somewhere else.

If you’re from some other “nice” place in America, New York is all sidewalk, all sharp corners, and all people in a crazy rush. A gestalt of motion and indifference. With a ubiquitous, acrid smell of leaking garbage.

Then you go down in the subway where the tile is resonating with noise. Utter noise. Announcements blasting from speakers. Shouting. Scuffling-shuffling shoes. Squeaks. Squawks. Clangs. Shouts.

In the middle of things, some guy’s doing this “sexy” Latin dance with a “sexy” girl puppet attached to him with these hinged poles. As he churns his hips, she churns hers, except the mechanism exaggerates her movements. The ass-shaking is really perverse. He’d set up the mechanism to force his partner to exaggerate his idea of how he wants a woman to dance. He’s gliding around making her contort so grotesquely that it’s like watching him rape a doll in front of a crowd. All to this distorted samba music blasting out of a speaker, the horns just cutting through your skull.

So I push through this mob and get on the shuttle.

I had decided to go the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Like I was sleep walking.

And there I was on the shuttle, quivering at the end of sanity. Then here comes this troll in a canary yellow Crazy Eddie t-shirt bellowing his lungs out: “DOES ANYONE KNOW HOW TO GET TO 23 PARK AVENUE?!?!”

I felt that I was about to lose my mind. That I had lost it.

This hideous ogre screaming at the top of his lungs and incapable of hearing any sensible answer was an externalization of my own panic, despair and insanity. To be trapped and powerless on that subway with a shouting idiot … this was my life.

Now someone is taking another shot at helping him. We all understand the game: do not mention Grand Central.

“Listen, buddy,” a lean, middle-aged black guy slowly, slowly spells it out. “You have to get off this train when it stops …”

“WHERE DOES THIS TRAIN STOP?”

“It doesn’t matter, you just get off. Do you understand?”

“I need to get off this train?”

“You HAVE to get off. The train doesn’t go anywhere else.”

“Where does it go?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“Why not?”

“Because you need to get another train.”

“Another train?”

“A transfer.”

“A transfer?”

“Yes, you’ll need to walk through the station …”

“Which station?”

“Gr … It doesn’t matter. You’ll walk through the station to ANOTHER train.”

“I have to go to another train?”

“Right.”

“A transfer?”

“Yes, you need to transfer.”

“Ohhhh. Okay. I transfer!”

“That’s right! You transfer.”

“To another train.”

“To another train.”

“Okay. Huh. Then where does this train go?”

Crazy Eddie finally sounds sane. Sort of. I mean, it sounds like, now that he grasps the concept that he needs to find a different train, he genuinely wants to understand where the shuttle is going. You know, he had the wrong idea about the shuttle. Now that he really understands that it doesn’t go to 23 Park Avenue, he has a quite reasonable desire to know where the shuttle does in fact stop.

The whole listening car realizes that this is how it sounds to this helpful gentleman.

Not to us. We all are dying to scream “DON’T SAY IT!”

But let’s face it. What a little victory it will be for this gentleman if Crazy Eddie responds calmly. Yes, I won! he can say.

But we all know what’s coming. Don’t say it, don’t say it, don’t say it!!!

But the man speaks. He sounds like a father adopting a “you’re old enough to hear this” tone with a child. I’m trusting that you’re ready to hear this.

“Well, this is the crosstown shuttle … and the last stop … coming up … this last stop is Grand Cen—”

“I DON’T NEEEEEEEEEEEED GRAND CENTRAL!!!! DOES ANYONE KNOW HOW TO GET TO 23 PARK AVENUE?”

Now Crazy Eddie sees we’re entering the station.

“WHAT STATION IS THIS? WHAT STATION IS THIS?”

Near him, a kind-looking older lady, tiny with short white hair like a nun, has a glint in her eye. As if overcome by the first faint approximation of a devious impulse in her entire life. She understands the power she has in this moment. The power of words. The temptation to use that power is too great to resist.

“WHAT IS THIS STATION?!?!?!” Crazy Eddie shrieks.

She says, “Ohhhh … why this …” She leans closer and really shouts. “This is … GRAND CENTRAL.”

Everyone can see Robert Crumb lightning bolts of shock form a halo around Crazy Eddie’s contorted face.

He takes in a deep breath as the doors open, and, as one thunderous unified chorus, the whole car shouts along with him: “I DON’T NEEEEEEEEEEEEED GRAND CENTRAL!!!!”

Of course, I’m laughing. Five minutes ago, I would’ve swallowed a bottle of sleeping pills in a Jersey Howard Johnson’s. Now I’m laughing.

But it’s not sane laughter. I didn’t suddenly see my woes in a “new perspective.” I didn’t suddenly realize things might not be so bad. I still wanted to swallow a bottle of pills. But I was laughing.

And there’s Crazy Eddie waddling along ahead of me. He’ll walk until he doesn’t know what to do. Then he’ll shout “DOES ANYONE KNOW HOW TO GET TO 23 PARK AVENUE?” Other New Yorkers will nudge him along. Eventually he’ll reach his destination. This may well happen once a month whenever he visits grandma on West End Avenue. Maybe his mother has told him to do this. Just scream until someone helps you. It could work for anybody.

Scream until someone helps you. Not the worst advice.

All New Yorkers are familiar with how the city just fucking assaults you with this sort of street theater. You didn’t ask for it, but here you go.

And the city doesn’t care if your heart is breaking. Here’s a guy juggling cats. The city doesn’t care if reality is falling apart like wet tissue. Here’s a lady in line at the DMV who drew her license with a crayon.

The playwright and madman Artaud talks about the cruelty of theater. I never knew what he meant until I noticed how New York, any day of the week, will shove these little plays right in your face. It’s cruel to tickle someone who is crying. But that’s what the city does.

Back down South, where I fled to sort out my shattered life, I realized that I missed this cruelty. I missed New York’s cruelty. I needed it. I couldn’t live without it.

And the thing is, and this is what I learned on that crosstown shuttle, the thing is how New York always scales up to meet your crisis. Have the hopes and dreams of your youth been smashed against the sidewalk? Here is a troll in a Crazy Eddie t-shirt screaming his lungs out.

On 9/11, we fled from my building across the street from the South Tower, orange flames curling from a huge zigzag gash high above. Trudging up along the FDR, we passed the Fulton Fish Market. The men were still working, chopping the fish. Getting it fresh to the market was more important than the end of the world. The Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph in my mind is a man in a white apron raising a knife in the air with the burning towers above him. Fish heads spread across the cobblestone.

New York is always bigger than anything else. Bigger than the end of the world.

This paradoxically makes you feel like you’re in a snow globe. Contained in the little toy universe.

I took a trip down South recently to visit my dad. I flew into New Orleans and drove up three hours to Madison, Mississippi. My return trip was very early so I drove back to New Orleans in the dark. After two hours of seeing only the white lines, the sky started growing pale, and I began to feel a terror rising in my chest. The huge, huge world! The world outside the goddamn snow globe. And then the sun rose blood orange above Lake Ponchartrain. A world way too big. I couldn’t wait to fly back to my snow globe, my subway from JFK sinking below Atlantic Avenue then letting me out in my little tilt-shifted toy world.